It’s taken a long time, but we’re finally publishing our paper about evaluating the Emotion Ontology (EM). Evaluating ontologies always seems to be hard. All too often there is no evaluation, or it ends up being something like “I thought about it really hard and so it’s OK”, or “I followed this method, so it’s OK”, which really amounts to not evaluating the ontology. Of course there are attempts made to evaluate ontologies with several appealing to the notion of “large usage indicates a good ontology”. Of course, high usage is to be applauded, but it can simply indicate high need and a least bad option. High-usage should imply good feedback about the ontology; so we may hope that high usage would be coupled with high input to, for instance, issue trackers (ignoring the overheads of actually issuing an issue request and the general “Oh, I can’t be bothered” kind of response) – though here I’d like to see typologies of requests issued and how responses were made.

Our evaluation of the Emotion Ontology (EM) fits into the “fitness for purpose” type of evaluation – if the EMdoes its job, then it is to some extent a good ontology. A thorough evaluation really needs to do more than this, but our evaluation of the EM is in the realm of fitness for purpose.

An ontology is all about making distinctions in a field of interest and an ontology should make the distinctions appropriate to a given field. If the ontology is doing this well, then an ontology delivers the vocabulary terms for the distinctions that need to be made in that field of interest – if we can measure how well people can use an ontology to make the distinctions they feel necessary, then the ontology is fit for purpose. In our paper we attempted to see if the EM makes the distinctions necessary (and thus the appropriate vocabulary) for a conference audience to be able to articulate their emotional response to the talks – in this case the talks at ICBO 2012. That is, the EM should provide the vocabulary distinctions that enables the audience to articulate their emotional response to talks. The nub of our null hypothesis was thus that the EM would not be able to let the audience members articulate their emotions such that we can cluster the audience by their response.

The paper about our evaluation of the EM is:

Janna Hastings, Andy Brass, Colin Caine, Caroline Jay and Robert Stevens. Evaluating the Emotion Ontology through use in the self-reporting of emotional responses at an academic conference. Journal of Biomedical Semantics, 5(1):38, 2014.

The title of the paper says what we did. As back-story, I was talking to Janna Hastings at ISMB in Vienna in 2011 and we were discussing the Emotion Ontology that she’d been working on for a few years and this discussion ended up at evaluation. We know that the ontology world is full of sects and that people can get quite worked up about work presented and assertions made about ontologies. Thus I thought that it would be fun to collect the emotional responses of people attending the forthcoming International Conference on biomedical Ontology 2012 (ICBO), where I was a programme co-chair. If the EM works, then we should be able to capture self-reported emotional responses to presentations at ICBO. We, of course, also had a chuckle about what those emotions may be in light of the well-known community factions. We thought we should try and do it properly as an experiment, thus the hypothesis, method and analysis of the collected data.

Colin Caine worked as a vacation student for me in Manchester developing the EmOntoTag tool (see Figure 1 above), which has the following features:

- It presented the ICBO talk schedule and some user interface to “tag” each talk with terms from the EM. The tags made sentences like “I think I’m bored”, “I feel interested” and “I think this is familiar”.

- We also added the means by which users could say how well the EM term articulated their emotion. This, we felt, would give us enough to support or refute our hypothesis – testing whether the EM gives the vocabulary for self-reporting emotional response to a talk and how well that term worked as an articulation of an emotion. We also added the ability for the user to say how strongly they felt the emotion – “I was a bit bored”, “I was very bored” sort of thing.

- We also used a text-entry field to record what the audience members wanted to say, but couldn’t – as a means of expanding the EM’s vocabulary.

We only enabled tagging for the talks that gave us permission to do so. Also, users logged in via a meaningless number which were just added to conference packs in such a way that we couldn’t realistically find out whose responses were whose. We also undertook not to release the responses for any individual talk, though we sought permission from one speaker to put his or her talk’s emotional responses into the paper.

The “how well was the EM able to articulate the necessary emotion you felt?” score was significantly higher than the neutral “neither easy nor difficult” point. So, the ICBO 2012 audience that participated felt the EM offered the appropriate distinctions for articulating their emotional response to a talk. The bit of EmOntoTag that recorded terms the responders wanted, but weren’t in the EM included:

- Curious

- Indifferent

- Dubious

- Concerned

- Confused

- Worried

- Schadenfreude

- Distracted

- Indifferent or emotionally neutral

There are more reported in the paper. Requesting missing terms is not novel. The only observation is that doing the request at the point of perceived need is a good thing; having to change UI mode decreases the motivation to make the request. The notion of indifference or emotionally neutral is interesting. It’s not really a term for the EM, but something I’d do at annotation time, that is, “not has emotion” sort of thing. The cherry-picked terms I’ve put above are some of those one may expect to be needed at an academic conference; I especially like the need to say “Schadenfreude”. All the requested terms, except the emotionally neutral one, are now in the EM.

There’s lots of data in the paper, largely recording the terms used and how often. A PCA did separate audience members and talks by their tags. Overall, the terms used were of the positive valence “interested” as opposed to “bored”. These were two of the most used terms; other frequent terms were “amused”, “happy”, “this is familiar” and “this is to be expected”.

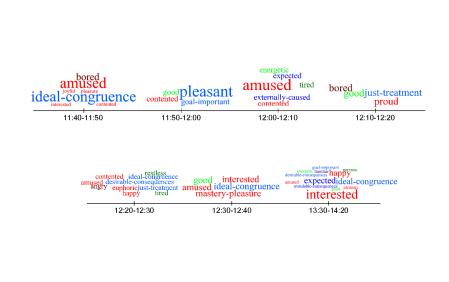

The picture below

Shows the time line for the sample talk for which we had permission to show the emotional responses. Tags used were put into time slot bins and the size of the tags indicates the number of times that tag was used The EM appraisals are blue, the EM’s emotions are red and the EM’s feelings are green. We can see that, of the respondants, there was an over-whelming interest, with one respondant showing more negative emotions: “bored”, “bored”, “tired”, “restless” and “angry”. Of course, we’re only getting the headlines; we’re not seeing the reason or motivation for the responses. However, we can suspect that the negative responses mean that person didn’t like the presentation, but that there was a lot of interest, amusement and some pleasure derived from understanding the domain (“mastery pleasure”).

We think that this evaluation shows that the EM’s vocabulary works for the self-reporting of emotional response in an ontology conference setting. I’m prepared to say that I’d expect this to generalise to other settings for the EM. We have, however, only evaluated the ontology’s vocabulary; in this evaluation we’ve not evaluated its structure, its axiomatisation, or its adherence to any guidelines (such as how class labels are structured). There is not one evaluation that will do all the jobs we need of evaluation; many aspects of an ontology should be evaluated. However, fitness for purpose is, I think, a strong evaluation and when coupled with testing against competency questions, some technical evaluation against coding guidelines, and use of some standard axiom patterns, then an evaluation will look pretty good. I suspect that there will be possible contradictions in some evaluations – some axiomatisations may end up being ontologically “pure”, but militate against usability and fitness for purpose. Here one must make one’s choice. All in all, one of the main things we’ve done is to do a formal, experimental evaluation of one aspect of an ontology and that is a rare enough thing in ontology world.

Returning to the EM at ICBO 2012, we see what we’d expect to see. Most people that partook in the evaluation were interested and content, with some corresponding negative versions of these emotions. The ontology community has enough factions and, like most disciplines, enough less than good work, to cause dissatisfaction. I don’t think the ICBO audience will be very unusual in its responses to a conference’s talks; I suspect the emotional responses we’ve seen would be in line with what would be seen in a twitter feed for a conference. Being introduced to the notion of cognitive dissonance by my colleague Caroline jay was enlightening. People strive to reduce cognitive dissonance; if in attending a conference one decided, for example, that it was all rubbish one would realise one had made a profound mistake in attending. Plus, it’s a self-selecting audience of those who, on the whole, like ontologies, so overall the audience will be happy. It’s a pity, but absolutely necessary, that we haven’t discussed (or even analysed) the talks about which people showed particularly positive or negative responses, but that’s the ethical deal we made with participants. Finally, one has to be disturbed by the two participants that used the “sexual pleasure” tags in two of the presentations – one shudders to think.